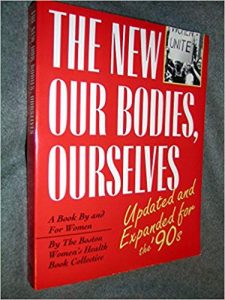

In the early 90s, I belonged to one of those book clubs that shipped you books every month if you didn’t tell them not to. Their business model depended on people like me, lazy people who forgot to send the “no thanks” postcard back in time. So, one month, due to my inaction, a book called The New Our Bodies, Ourselves Updated for the 90s showed up at my door.

In the early 90s, I belonged to one of those book clubs that shipped you books every month if you didn’t tell them not to. Their business model depended on people like me, lazy people who forgot to send the “no thanks” postcard back in time. So, one month, due to my inaction, a book called The New Our Bodies, Ourselves Updated for the 90s showed up at my door.

I wasn’t yet a Women’s Studies minor at the state school where I’d eventually eke out a degree through late night classes and CLEP tests. I had a vague sense that womanhood was fraught with issues that manhood was not, but I fancied myself mostly a man’s woman, not one to whine about inequality and misogyny. I believed in the equivalent of “by the bootstraps” thinking on gender roles… if you didn’t let them, the bastards couldn’t get you down.

So, at first, nothing but a prurient interest caused me to peek inside the book. It sure wasn’t feminist zeal. I’d had all the health classes, and even some modest real-world experience, but the book was so thick, and had chapters on things it had never even occurred to me to think about, so I just had to look. Soon I discovered there was something different about it. I didn’t know it at the time, but its authors, formally listed as The Boston Women’s Health Book Collective, were a group of six feminist activists who were unhappy with the state of medical information available to women in the late 1960s, and to the restrictions this lack imposed on women’s lives. They believed that “information about one’s body is perhaps the most essential kind of education, because ‘bodies are the physical bases from which we move out into the world.’ Without this basic information, women are alienated from their own body and necessarily on unequal footing with men.”

I read it cover to cover, although, as a reference book, I’m not sure that it was intended to be read that way. I read about gonorrhea and menopause, about sexual identity. I read what to my Catholic-school eyes was a shockingly liberal point of view of women’s sexuality, desires to be owned and celebrated instead of repressed. I learned history about the movement to provide women with birth control. I read it over and over again, mesmerized, surprised, and at times repulsed.

Of the many things that emblazoned themselves in my brain about this book, the one that stands out most was in the section about body image. In the early 1990s, I was in my early 20s, at the height of my physical attractiveness, although I didn’t know it. I obsessed constantly about the ugliness of my upper arms (a few teenage pimples had left what I thought were disfiguring scars, and I steadfastly refused to wear anything that exposed my shoulders), and about how as a size 0 I still wasn’t quite as thin as I wanted to be, not nearly as skinny or beautiful as the models I revered in Vogue and Cosmopolitan. I still took up too much room in the world for my taste and I longed to erase more of myself.

In this section about body image, there was a black and white picture of a naked female torso. The caption said something about how this was an example of what a real human female looked like, and how air-brushing and stylizing led women to think their bodies should look different than they do, but that the picture was closer to the truth. The body was a little flabby, with a giant, unkempt bush, and enough fat in the belly to create a little pouch which had lost its fight with gravity.

The first time I saw that picture, I burst into tears. My twenty-something-year-old body, as taut and perky as it would ever be (I later realized), was already so intolerably far from what I wanted it to look like, that the idea of ever being so grotesque was more than I could bear. On subsequent readings of the book, I hissed past that page as a tribeswoman might walk past the site of a grisly death, never turning her back, lest a dark fate befall her, too. It haunted me and horrified me. I could never live in anything so flawed.

You know where this story is going. Years passed. Babies came, and did a number on my belly. My thighs grew stretchmarks, first angry red welts, then silvery, forlorn memories. My belly also lost its fight with gravity, in tandem with my boobs. Hairs began sprouting where none had grown before, and the ones on my head increasingly lost the fight with the pigment gods. I got older. Fatter. Flabbier. The body that had once seemed the absolute bare minimum became the fond memory, the hoped-for ideal. If only I could go back and tell that twenty-two year old woman how damn gorgeous she was, and make her believe me.

But, then, of course, being kept from the knowledge of the value of what we have is one of the ways we can be kept weak. I didn’t have the length of bone for a modeling career, but I had fingers that could type like lightning, and legs that pumped strong despite all neglect. I had a dogged health and a curious mind, and calves that weren’t half bad, and hair that was fun to curl. No, physical beauty isn’t everything, but acceptance of oneself is, and I have fought a long battle against it, a civil war, losing on both sides.

It is hard to be a woman in our world. It is probably harder to be a woman losing the thing our society values most: sexual appeal to men. But it is exhausting to be constantly evaluating oneself as a commodity, watching stock rise and fall in a market that is rigged. It is sad to look at a picture of a perfectly average body and cry. It is worse to see your own body in the mirror, and realize it’s turned into the one in the pages of the book, and feel anything but love. I have never had great skill in the area of self-love, but I do know it begins with truth, with an unflinching view of what is. This is me, the home I reside in. I began the journey to learning how to love it in the pages of a long-lost book, as so many journeys before and since. The journey continues. I am flawed, and glorious, and sad, and hopeful. I am me, and it has to be amazing, because it’s all I can be.